An old roommate of mine worked for a company that organized trade conferences, and one day he came home from a publishing conference with a pile of free books. “You like books, right? Here…” I sold some of them on Amazon and gave others to Goodwill, but one I hung on to was Heavy Rotation: Twenty Writers on Albums that Changed Their Lives. I carried that book to two more houses without actually reading it, but was never quite able to throw it in the donation pile.

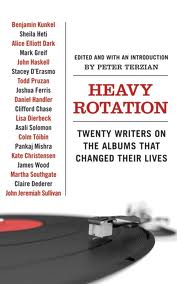

But finally, perhaps too lazy to go to the library and too cheap to go to Barnes and Noble, I picked it up from its undistinguished spot in the bookshelf overflow pile and started reading. The 2009 essay collection appealed to the teacher in me who wished she had a more glamorous job: rock star, music journalist, rock star… Each essay detailed an album that influenced the author at an impressionable time in his or her life. Edited by Peter Terzian, the collection spanned many genres, discussing music from early Americana to Gloria Estefan to unknown British punk bands.

But finally, perhaps too lazy to go to the library and too cheap to go to Barnes and Noble, I picked it up from its undistinguished spot in the bookshelf overflow pile and started reading. The 2009 essay collection appealed to the teacher in me who wished she had a more glamorous job: rock star, music journalist, rock star… Each essay detailed an album that influenced the author at an impressionable time in his or her life. Edited by Peter Terzian, the collection spanned many genres, discussing music from early Americana to Gloria Estefan to unknown British punk bands.

I hadn’t listened to many of the albums that were featured, but that didn’t detract from my enjoyment of the essays. The point wasn’t so much musical dissection or analysis as to explain how each particular record spoke to the person writing about it. Often, the essays were tales of growing up; one author, Clifford Chase, listens to the B-52s self-titled album while coming to terms with his homosexuality — before the days of gay rights and the It Gets Better Project. Another author, Asali Solomon, finds solace in the familiarity of Gloria Estefan’s Mi Tierra – which she had hated at first – while on a hellish semester abroad in the Dominican Republic.

One of my favorite essays was Terzian’s contribution “Nine Lives,” about the British punks Miaow and their never-released album Priceless Innuendo. I looked up Miaow (http://lilypadrecords.com/Lilypad/Miaow.html) on the internet and couldn’t even stand listening to an entire song. Terzian was obsessed with them, though, to the point of tracking down vocalist Cath Carroll, developing a friendship with her, and begging her to send him his Holy Grail: unreleased Priceless Innuendo tracks.

Well, she never sent them. In fact, she told Terzian that she’d unearthed the old cassettes , “listened to the songs, and cringed.” Twenty years after the fact, the tracks have been posted on Myspace and a restoration is available from Lilypad Records — aptly titled Priceless Restoration, not that I’ll be buying it any time soon.

What I loved about this essay was not finding out all about Miaow, but reading how Terzian described his wannabe-hipster college-aged self. He writes, “I had formed a mental picture of the kind of guy I wanted to be, the kind of guy I looked up to: the musical sage, with five, maybe six such full crates (records were always kept in crates, on the floor; you had to kneel to look through them), synapses firing with titles of b-sides and production credits, the self-satisfied owner of out-of-print gatefold limited edition singles and flexidiscs […] I believed that by shedding my crisp turquoise Ralph Lauren Polo shirts and donning a pilly old mohair sweater with sleeves that fell over my hands, I had finally revealed my true self.” It made me nostalgic for the age – early teens to early twenties? For me, at least — when self-actualization could be achieved through music and a t-shirt.

What I loved about this essay was not finding out all about Miaow, but reading how Terzian described his wannabe-hipster college-aged self. He writes, “I had formed a mental picture of the kind of guy I wanted to be, the kind of guy I looked up to: the musical sage, with five, maybe six such full crates (records were always kept in crates, on the floor; you had to kneel to look through them), synapses firing with titles of b-sides and production credits, the self-satisfied owner of out-of-print gatefold limited edition singles and flexidiscs […] I believed that by shedding my crisp turquoise Ralph Lauren Polo shirts and donning a pilly old mohair sweater with sleeves that fell over my hands, I had finally revealed my true self.” It made me nostalgic for the age – early teens to early twenties? For me, at least — when self-actualization could be achieved through music and a t-shirt.

But time marches on, people grow up, and “the Internet changes everything.” Terzian eventually graduates college and moves up the ladder from menial jobs to becoming a professional writer. And thanks to Amazon and downloading, he can accomplish his goal of becoming an erudite music hipster: “Every out-of-print album and lost b-side, every demo track and unreleased alternate version that I’d ever read about and thought I’d never get to hear has found its way onto my hard drive. Without much effort, I became the musical sage I so aspired to be.”

This leads me to my other favorite essay: “O Black and Unknown Bards” by John Jeremiah Sullivan, about American Primitive Volume II: Pre-War Revenants. Anybody that I’ve forced to listen to my old Backwater Racket EP or so-called “kite music” (long story: Two Gallants, etc.) knows that I enjoy folk music. There’s something meditative about playing and listening to songs that have been sung for hundreds of years, or even modern songs that are stylistically based on older ones. It connects listeners to a time before instant communication and good healthcare — when it was common to bury lovers and children, when people weren’t entertained by screens, when you couldn’t Facebook your friends stationed overseas. This acute closeness to death and separation – with no TV or computer screen to distract from reality, no Angry Birds to keep the mind from wandering — produces haunting, emotional music that is , in my opinion, more intoxicating than the most technical solo Yngwie Malmsteen can coax out of his sausage fingers…

In “O Black and Unknown Bards,” Sullivan is on a quest to bring such music to the public. He works as a music magazine editor and is charged with deciphering lyrics to a track on American Primitive Volume II: Geeshie Wiley’s “Last Kind Words.” Wiley is a mysterious character; nobody knows where she was born or where she’s buried, and no photos of her exist. All that’s left of Wiley are six poignant and distinctively arranged blues songs, and all the internet in the world won’t change that. I was also captivated by Sullivan’s discussion of recording history and lyrical etymology. Variations of stock blues verses have worked their way into many artists’ music; although it’s impossible to know who first sung those verses, it’s interesting to read about the first time the words were recorded and what those words actually mean.

So, now all we have to do to be “musical sages” is sit in front of our computers and download albums… But there was once a time when people scoured record stores to become sages – and decades before that, a time when the only way to hear new music was to be in the same room as someone playing it. Heavy Rotation: Twenty Writers on Albums that Changed Their Lives reminded me of why I got into playing music in the first place: I had heard songs that moved me, and wanted to be a part of creating something that had the same effect on other people. It’s not about Facebook likes or who’s “attending” your events – it’s about the feelings that music conveys.

As Claire Dederer writes in “Bewigged,” the final essay, “If you stripped your life down to a list of responsibilities, if you did only the things that needed to be done, what would happen to you? What would you become? I don’t know the name for the sickness reality brings, but I do know its cure: music, and friendship…”