“The first monster that an audience has to be scared of is the filmmaker. They have to feel in the presence of someone not confined by the normal rules of propriety and decency.” Wes Craven

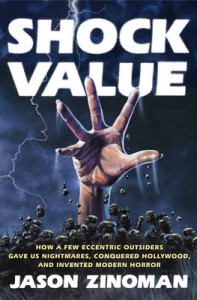

It is with this quote that Jason Zinoman opens his book, Shock Value: How a few eccentric outsiders gave us nightmares, conquered Hollywood, and invented modern horror. A pretty lengthy title, but an accurate one. In Shock Value, Zinoman, a New York Times theater critic and freelance writer, delves into the 1970s’ horror movie industry with a keen eye for detail and thorough analysis. His focus is on films and filmmakers that transformed horror from a laughable

It is with this quote that Jason Zinoman opens his book, Shock Value: How a few eccentric outsiders gave us nightmares, conquered Hollywood, and invented modern horror. A pretty lengthy title, but an accurate one. In Shock Value, Zinoman, a New York Times theater critic and freelance writer, delves into the 1970s’ horror movie industry with a keen eye for detail and thorough analysis. His focus is on films and filmmakers that transformed horror from a laughable

genre confined to B-movie status into a mainstream, profitable art form. If you are familiar with this time period, then you will probably be able to guess the films that are Zinoman’s main focus: Night of the Living Dead, Rosemary’s Baby, The Last House on the Left, The Exorcist, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Carrie, Halloween, and Alien. (If you haven’t seen all of these, your life is severely lacking.)

In the first chapter, Zinoman grabs the reader’s attention with a simple story that unfolds, fittingly, like a scene in a movie. It is the story of how Rosemary’s Baby was “born.” Opening with this story, Zinoman sets up his thesis on how horror transformed from what the critics call Old Horror into New Horror. Director and producer, William Castle, who owned the film rights to the novel, Rosemary’s Baby, was of the “old horror.” He directed films with fake plastic monsters (you can see the strings on some of the puppets) that starred Vincent Price. However Paramount felt that Rosemary’s Baby needed a fresh, new directorial style, so the job went to Roman Polanski. There are interesting seedy details to the story, but it symbolizes the passing of the torch from directors like Castle to directors like Polanski, who transformed the film industry.

What sets apart Old Horror from New Horror is, simply put, that New Horror breaks the rules. For instance, in Rosemary’s Baby, the devil wins, which was totally unheard of, but, not only that, you never see him. The fear is psychological. In The Last House on the Left, Craven brought violence that was more graphic and real than had ever before been seen on film, and coupled it with a story that blurs the line between the good guys and the bad guys. Again, messing with the audience’s mind. Just how these directors manipulate the audience is what makes Zinoman’s in depth analysis of these films compelling. I know what scares me, but I never knew exactly why. What about the meat hook scene in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre makes it one of the most shocking and memorable scenes in film history? There’s no blood!? Zinoman goes into detail explaining just what makes these films scary and innovative: camera angles, cuts, changes in point of view, etc. Some of the manipulation was to avoid an X rating (less blood, better rating). Some was simply due to lack funding, which forced the directors to be more creative in delivering their scares (this is part of what is lacking in modern horror).

Throughout the book, Zinoman tells the unusual stories of the making of these, now classic, films from creation to promotion. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is one of the most bizarre and entertaining stories in the book. It’s a horror film in itself: violence, decay, mental illness, and the mafia. Another interesting aspect of this book is how some of the directors and writers are connected, and how their relationships soured, blossomed, or clashed from the start. Sometimes, it is a wonder how any of these films were made at all, let alone released.

Zinoman writes like a novelist with a reporter’s zeal. Woven throughout the text are accounts from directors, producers, actors, etc. adding validity and substance to his analysis. He sees the connections between films that may not be obvious to others, explaining how they built upon and fed each other. Giving insight into the directors and their personal tastes (Romero hated Texas Chainsaw!), he examines how they were influenced by their personal histories and surroundings. It is clear that he has a deep respect and appreciation for the people involved in creating these films, and pieces together how these individual films recreated a genre. It was not as though all of these directors sat down together and set out to reinvent horror. It was one of those magical moments in time where, socially, politically, and personally, it all just came together.

This book gave me a new appreciation for films I already loved and films I can’t believe I haven’t seen (I now have a long list). You don’t need to have an extensive background in horror to appreciate this book, but it helps to know who people like William Castle and H. G. Lewis are (watch The Tingler and The Wizard of Gore) and what the Grand Guignol Theatre was. If you haven’t seen all of the aforementioned films, you should, whether you want to read this book or not. They’re just awesome movies!

Some recommended films for Halloween:

- Stacey (Japanese)

- Rigu (Japanese – the American version is crap),

- Fright Night (1985)

- Fido

- Nekromantic

- The Thing from Another World (1951 – inspiration of many directors)

- Nosferatu (1922 – can’t mess with a classic)

- Any monster movie with Bella Lugosi or Boris Karloff