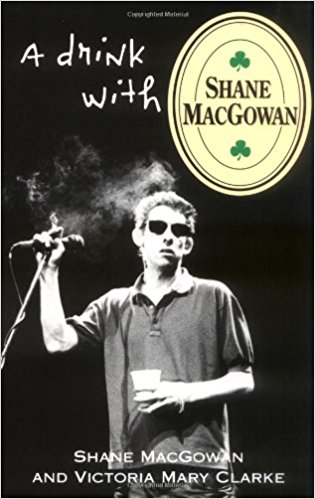

Much like the usual millennial, I came to know of Shane MacGowan through a random YouTube search. It was a video list of rock stars that should be dead, but aren’t. There were of course the expected culprits; Ozzy Osbourne, Nikki Sixx and Keith Richards. But then they mentioned this guy from an Irish group called The Pogues. He looked like an absolute mess, stumbling around drunk and drugged up with barely a few rotten teeth in his mouth. YouTube gave me a brief summary of his shenanigans, but I wanted to dig deeper. My wife luckily had a copy of his memoir, A Drink with Shane MacGowan.

First off, I’m usually not a reader of biographies. Every celebrity or person of interest, no matter how interesting of a personality, has certain stretches of their life that bore me. And frankly, I don’t have the patience to read through the parts that drag. But this book is constructed differently. The reader is a bystander to a series of private interviews between Shane and his wife Victoria. The book is split into eight separate acts, or conversations, taking place at different locations. These interviews are conducted by Victoria in a very loose and casual fashion. The couple sometimes get into little arguments, even veering off the subject to engage in small talk. The reader is subjected to all of this, getting a pretty in-depth look into their personal lives. And it’s made clear that the relationship isn’t always healthy. This gives the book a very raw, human, and unsteady quality, and I appreciated the lack of stoicism in the narrative.

The meat of the book consists of questions about Shane’s upbringing, his philosophy, his roots with punk rock and his time with The Pogues. Shane himself is usually all over the place, so Victoria has to occasionally play referee and get him back to the subject at hand. Many of his statements are intelligent, filled with honest self-awareness, biting criticisms and deep thoughts about a host of subjects including music, politics, religion, books and movies. His opinions are sometimes controversial, especially when talking about the IRA, drug-use, and his unconventional views on the U.K punk rock movement, of which he was very much a part of. At times he’s also contradictory, a bit rude and apparently caught in a loop of intoxicated rambling. This makes his encyclopedic historical knowledge pretty surprising, given that he’s spent pretty much his entire life as a drunk. He recalls very particular memories about people he’s shared a drink with, fights he’s been in, family disputes and imaginative daydreams he had as a child. He provides a very insightful profile of himself both as a rock star and as a private person – so much so that after reading this, I felt like I knew him personally, even though I’ve yet to even listen to a Pogues song in full.

My favorite part of the book is probably his insight into the roots of the British punk movement. While reminiscing about his part in the early punk scene, he debunks any of punk rock’s supposed associations with political or social movements. He explains the phenomenon for what it really was: nihilism. Punk was a short-lived moment of nihilistic youth behavior. They didn’t give a fuck about politics, the future or representing anything other than living in the moment. It was about doing whatever you wanted without considering the consequences. Have sex whenever with whomever; do all the drugs, drink, fight, mock authority and play noisy music. Playing in bands and working at record stores kept a modest cash flow coming in to support the kids’ hedonistic lifestyle, and that’s all they needed. It sounds very anarchic, and it was. But it was also incredibly free and harmonious.

In Act 4, Shane describes the gender equality of punk. Men and women were viewed as equals, willing to fuck and fight and rage as physical human beings. Controversial social views were satirical fashion statements. Swastikas and fascist symbolism were present just as commonly as anti-racist and anti-skinhead slogans. It was all a running mockery of the establishment; a rebellion against everything. It was a group of young people that were tired of politics and war and flower-power and the pressures of economic recession. It was a movement that according to Shane, lived and died within the course of eighteen months and never rematerialized in an honest fashion. For him, as soon as hippies and preps started embracing the movement, it became a constructive vehicle of ideals and lost its potency. Bands like The Clash and The Talking Heads diluted the mix. What’s interesting about all this is the fact that Shane offers an argument against the mainstream critical analysis of the punk movement. As a musician who avoided the attention of the masses, he’s under no pressure to offer pretenses about who he is as a person or about his place in rock music. He and many other punks liked to drink and fight and be creative. That’s what it was about.

All in all, I really enjoyed reading this memoir. Shane is funny, a little crazy, intelligent and informative. The interplay between him and his wife is amusing, and the unpredictability of their conversations keeps the book from dragging. There were a few subjects that weren’t as fascinating to me as others, but that’s really a matter of subjective opinion. I recommend it to both fans and strangers to the man’s work. He’s quite a unique character and a person worth learning about.

For more from Alternative Control, find us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and bandcamp.