It doesn’t take a Pulitzer winner to see that media has changed since the advent of the internet. Publication mediums have shifted, advertising has increased on free services, and “click-bait” often rules over well-crafted or thoroughly vetted content. On the positive side, the internet has allowed media companies to innovate how they deliver content to their consumers, among other things.

Radio is no exception to these changes. No longer stuck with a dial full of tired classic rock stations, music enthusiasts can choose from subscription services like Sirius, free music from Pandora and Spotify (with the option to upgrade to an ad-free service), a myriad of internet radio stations, and even internet versions of terrestrial stations. But with all these options come a tangle of legal issues that have recently resulted a big problem for small internet radio stations. This big problem has a name: the Fair Play Fair Pay Act of 2015, or HR-1733.

The long version of this law and its history took my friend and much-loved local webcaster Bob “Knob” Marino about three pages to explain — and then another twelve emails to answer my questions. The short version is that before HR-1733 took effect on January 1, 2016, a law known as Webcaster II governed royalty payments. From 2007-2015, provisions in Webcaster II kept costs within reason for hobbyists with a small number of total listening hours (the amount of time that people are actually tuning into a station); the webcasters still paid royalties to the artists, but it was in proportion to their reach. Keep in mind that at this time, terrestrial radio paid no royalties.

There were some inequities within Webcaster II that needed to be changed. Artists whose songs were played millions of times on streaming services were getting compensated practically in pennies — for instance, in 2014, Bette Midler reported that she got paid $114 from Pandora and Spotify for over 4 million plays of her songs. And there was the fact, as I mentioned above, that terrestrial radio paid nothing to artists at all.

HR-1733 fixed some of these problems. Pandora will now pay more equitable royalty rates, as will terrestrial radio. (Spotify has a loophole because listeners pick specific songs, but that’s another article.) However, there are no special provisions in HR-1733 for small commercial and non-commercial webcasters. Their rates have gone up, in many cases beyond the income they are able to generate — or for hobbyists, more than what they can afford to pay out of their own pockets.

Take Knob, for example. Official FN Radio gets about 70 total listening hours a month — a minute drop in the vast ocean of online radio listening. For the privilege of sharing with his friends the local music he loves, he’d previously been paying about $20 per month in royalties, in addition to whatever he pays for hosting services, the chat feature on his site, etc. Since HR-1733 took effect, his royalty charges have been around $60 per month — which if he continues with his current format, will add up to over $700 per year. That’s not an insignificant amount, especially for the head of a family with children that’s operating on one income. It’s certainly more than I’d ever pay out of pocket to run Alternative Control. And when it’s groceries or the radio station, you know which one will go.

Another example within our extended circle is Bullspike Radio, run by brothers John and Josh Shatesky. Their station was part of an online radio service called Live365, which provided a platform for over 5,000 independent stations around the globe. OFNR was even part of the Live365 network for a time, and Knob said that it “let (him) be an entrepreneur and grab the reins.” But the network shut its metaphorical doors due to HR-1733’s royalty rates, leaving Bullspike Radio and thousands of other stations to find their own servers and pay their own royalties. John reports that Bullspike’s monthly listening hours have dropped from 80 to 20 since they have lost Live365’s distribution services.

Another example within our extended circle is Bullspike Radio, run by brothers John and Josh Shatesky. Their station was part of an online radio service called Live365, which provided a platform for over 5,000 independent stations around the globe. OFNR was even part of the Live365 network for a time, and Knob said that it “let (him) be an entrepreneur and grab the reins.” But the network shut its metaphorical doors due to HR-1733’s royalty rates, leaving Bullspike Radio and thousands of other stations to find their own servers and pay their own royalties. John reports that Bullspike’s monthly listening hours have dropped from 80 to 20 since they have lost Live365’s distribution services.

HR-1733 is also changing the game for commercial sites like Connecticut’s Metal Fortress Radio. According to founder Christina Palmer, known on the station as Lady Rose, their first royalty bill this year was around $400 for 5,300 listening hours. While she is happy to pay the artists, the new rates mean that she and partner Tommy “The Beast” Blardo will no longer be able to subsidize the station with income from their landscaping business — they will have to seek more advertising and sponsorships to keep the station growing. When I spoke with Lady Rose on the phone this morning, she sounded confident that Metal Fortress would be able to fund its growth, but acknowledged that it was a big shift from how the station started out.

Webcasters like Knob, the Shatesky brothers, and Lady Rose are avid supporters of local music, so it would hurt me in a self-interested sense if their radio stations shut down due to lack of funding. I’m sure this sentiment is shared by many in the Connecticut metal and rock scene; we want the few people who promote our music for free to continue doing so.

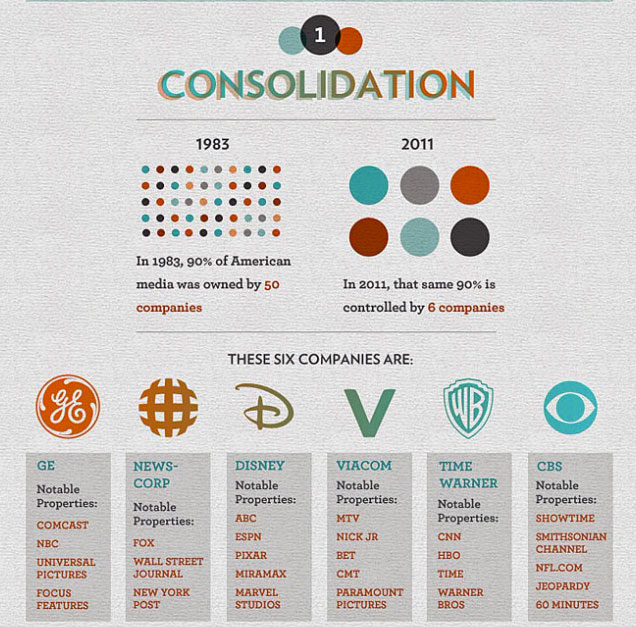

But in the broader picture, the strangling of small webcasters is part of an overall consolidation and homogenization of the media. This graphic from Policy Mic explains how a very small number of companies control almost everything Americans read, watch, and listen to:

(Edit: In 2013, Comcast purchased NBCUniversal from GE, following a 2009 deal where Comcast bought 51% of that company from GE. More from Wikipedia, verified by other sources: “NBC Universal was formed on May 12, 2004 by the merger of General Electric‘s National Broadcasting Company with Vivendi‘s Vivendi Universal Entertainment. GE and US cable TV operator Comcast announced a buyout agreement for the company on December 3, 2009. Following regulatory approvals, the transaction completed on January 28, 2011. Comcast subsequently owned 51% of NBCUniversal while GE owned 49%. Comcast intended to buy out the rest of GE’s stake over the following seven years, but nothing happened until February 12, 2013, when Comcast announced its intention to complete the purchase all at once and assume 100% ownership of the company by the end of March. The deal was finalized on March 19, 2013.” Looks like we need a more recent infographic with Comcast on it.)

As the Portland Radio Project put it, “(Radio consolidation) matters because it minimizes choice in radio programming, taking away the opportunity for local bands and artists to share their music with their community. It matters because local stations are no longer authentically local; generic broadcasts repeated in city after city frame the listener experience.” Stations like OFNR and Bullspike were an answer to that consolidation, but their future is now looking dim. And Metal Fortress will take a lot of work this year to remain in the black.

Meanwhile, companies like Texas-based iHeart Media are running thousands of AM and FM stations across the country. Formerly known as Clear Channel, iHeart is a subsidiary of Bain Capital, which pulls in over 75 billion dollars a year in revenue and also owns The Weather Channel, Bain Capital Ventures, and many more. Trust me, your metal band isn’t even a speck of dirt on Bain Capital’s shoe. (Edit: And guess who else is part-owner of The Weather Channel? Comcast.)

In Connecticut, Petrus Holding Company now owns at least six AM and FM stations, including 95.9, 99.1, 102.9, and 99.9, after buying out Westport-based Connoisseur Media in July 2015. (Which in addition to its CT stations, owned stations in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Kansas, and Montana.) According to the Dallas Business Journal, “Petrus Holding Co. is a private business holding vehicle for the Perot companies. The company partners with management teams to own middle-market companies across industries.” (Edit: Petrus retained Connoisseur’s management in the deal.)

Yes, Perot like Ross Perot — one of the 200 richest people in the United States, with his son who runs Petrus not far behind him. I promise the Perot family and their middle market companies don’t care about your metal band either. In fact, I was employed as a freelance writer by CTBoom.com from 2014-2015, which was owned by Connoisseur Media, which is now owned by Petrus but still purports to be “locally owned by Connoisseur Media”…. One of my frequent topics was the local music scene. But in early 2015, Connoisseur did away with their freelance budget. I’m not sure if the decision was related to their upcoming acquisition by Petrus (or perhaps an article Alternative Control ran maligning the Chocolate Expo, long story), but the timeline is compelling. In any case, my editor said that it had nothing to do with the content I was turning in and I’d like to believe him. But whatever the reason, I lost access to a much larger platform than Alternative Control, plus a nice chunk of change in my bank account.

However, my personal qualms aren’t the issue here. The issue is that like everything else in this country, more and more of the media is being controlled by fewer and fewer people. So what can you, the music lover, do to keep your favorite small radio stations playing? First, you can put your money where your mouth is. Contribute to your station’s GoFundMe projects. Attend their events. Buy their merch. Become a member of stations instead of just a passive listener. (WFUV! Not a small station but still in need of support to keep the great tunes spinning.) Also, you can sign this petition to show your support for changes to HR-1733 that would keep hobbyist webcasters on the air.

Take action now — before every creative outlet you love has been bought out, squeezed out, and stamped out completely.

Be sure to find Official FN Radio, Bullspike Radio, and Metal Fortress on Facebook.

For more from Alternative Control, find us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Soundcloud, and bandcamp.

The statement that terrestrial radio stations have been paying no royalties is not entirely true. They have been. They pay ASCAP, BMI and SESEC royalties for each song played, but it’s not a performance royalty. Instead, it’s a royalty that goes to the songwriters, but not the performers.

Web broadcasters, however, do pay performance royalties. Terrestrial radio stations in other countries do pay performance royalties, but they usually have blanket royalty arrangements that cover both artists and performers. They manage to do this without going broke, and the proponents of U.S. licensing companies complain that European radio stations do not go broke. They do not, however, pay the same rates we do. The U.S. is noteworthy for having the highest music royalty rates of any country in the world.